By Rosanna Haroutounian in Quebec City

Racial profiling by police is not a new phenomenon. The ability to now document aggression by law enforcement against African Americans and other racialized people and broadcast the footage around the world makes this long-standing injustice hard to ignore.

Along with meaningful discussions though, these images are also sparking retaliation by some members of the targeted communities.

These acts of aggression, the feelings they create, and the history they are grounded in, are hard for adults to understand, let alone explain to a young person.

Thanks to the Internet and technology, children and youth today have the world at their fingertips. Yet defining how prejudice and racism continue to have implications in different realms of society are ongoing topics of research, policy discussions and public debate.

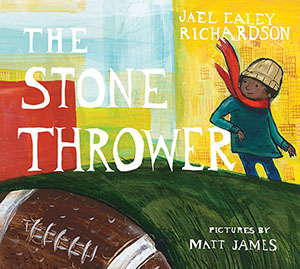

Books like The Stone Thrower by Canadian author, Jael Richardson, are one way to start a conversation with children about the historical roots of some of the prejudice we continue to see today against African Americans.

The illustrated book tells the real-life story of Chuck Ealey, starting from when he was born in Portsmouth, Ohio, in 1950. He grows up in the city’s North End neighbourhood without most of the opportunities that many other children in America enjoy.

The illustrated book tells the real-life story of Chuck Ealey, starting from when he was born in Portsmouth, Ohio, in 1950. He grows up in the city’s North End neighbourhood without most of the opportunities that many other children in America enjoy.

Because of racism against Black people in America — which often revolves around the idea that all Black people have characteristics that make them inferior to Caucasian Americans — Chuck and other people who have black skin must live, learn and play separately from those with white skin.

Chuck’s mother works long hours for little money, yet still has time and energy to instill in her son the drive to get educated and follow the train tracks that go beyond the North End.

“How could he get out of the North End if they didn’t even have enough money for food?” Chuck wonders.

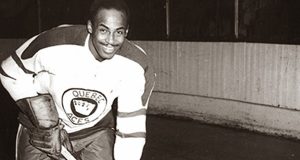

Chuck Ealey seen with the African Canadian Achievement Award for Excellence in Sports, which he received in February, 2013. Photo credit: ACAA.

He begins visiting the train tracks regularly to practise throwing stones at the passing freight cars. It helps him on the football field, and eventually his high school coach asks him to play quarterback during a game.

On the field, he is taunted by the rival team, but maintains his focus and determination to win.

The team’s victory is the start of Chuck Ealey’s long and successful career in high school and college football. After that, though, his time as a football player in the United States is over.

“The National Football League didn’t believe that he could be a great quarterback because of the color of his skin,” writes Richardson.

So instead, Ealey moved to Canada to play in the Canadian Football League (CFL). In his first year as a quarterback for the Hamilton Tiger-Cats, he led the team to the Grey Cup championship and was named the game’s Most Valuable Player and the CFL’s Rookie of the Year.

“It’s an unbeatable story that amazes me, even though I’ve heard it all before, because Chuck Ealey happens to be my father,” Richardson explains at the end of the book. She has also written about her father’s story in a 2012 memoir called The Stone Thrower: A Daughter’s Lesson, a Father’s Life, which was the subject of a TSN (The Sports Network) documentary.

Chuck’s story is remarkable, yet his experience with racism is not unique. Racial segregation was a reality for a huge segment of the population only about 50 years ago — in both the United States and Canada.

Children can relate to parts of the book about playing outdoors, practising sports and being part of a team. What might come as a surprise is that there was once a time when not all children could enjoy these things equally.

The Stone Thrower’s colourful and animated pages tell of a history that was much uglier, hateful and violent.

Chuck Ealey relaxes before receiving his award at the ACAA gala in February, 2013. Photo credit: ACAA.

While segregation was not enshrined in Canadian law, it still existed in all facets of social life. The story of Viola Desmond being arrested for sitting in the whites-only section of a New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, movie theatre is just one example.

These injustices continue to have repercussions that are felt today. While the days of slavery are over, poverty in Black communities and videos of police brutality against Black people are remnants of what U.S. President Barack Obama termed “the difficult legacy of race.”

The NFL can no longer bar Black athletes from playing football, but law enforcement, employers and the justice system are still realms in which race matters. The Stone Thrower is a reminder of how far we have come, and how far we have yet to go.

However, Ealey’s story is also a much-needed reminder for children and adults alike of what is possible when we work against division and towards inclusion. Through a basic retelling of how one man overcame injustice to be treated fairly, we see how difficult it is to explain and justify segregation and inequality.

On the other hand, we see how easy it is to defend everyone’s basic right to work, play and live without discrimination.

Reprinted from New Canadian Media

Rosanna Haroutounian is a freelance writer and the assignment editor at New Canadian Media. She studied journalism and political science at Carleton University and now splits her time between Quebec City and Peterborough, Ontario.

Pride News Canada's Leader In African Canadian & Caribbean News, Views & Lifestyle

Pride News Canada's Leader In African Canadian & Caribbean News, Views & Lifestyle